Level of education and religiosity in France and Britain: impacts on fertility?

In an article published in Population 2020-1, Nitzan Peri-Rotem analyses individual interactions between two major fertility determinants: education and religiosity or religious affiliation.

“During the latter half of the twentieth century, both Britain and France experienced a marked decline in the proportion of religiously affiliated persons and religious service attendance,” writes Nitzan Peri-Rotem. Meanwhile, educational levels continued to rise. Generally, these two phenomena—falling religiosity, rising education—imply lower fertility outcomes. Lengthy education can lead to postponing first births and/or reducing the number of children a woman wishes to have. And declining religiosity has gone together with falling fertility.

However, higher education and religiosity are not systematically opposed. In Britain, for example, religiously affiliated women have higher educational attainment: “the greatest proportion of highly educated women is found among practicing religious women”: 46% of women identifying as practicing Protestants have high educational attainment as against 33% of women with no religious affiliation. In France, however, 20% of Catholic women are highly educated as against 26% of women reporting no religion.

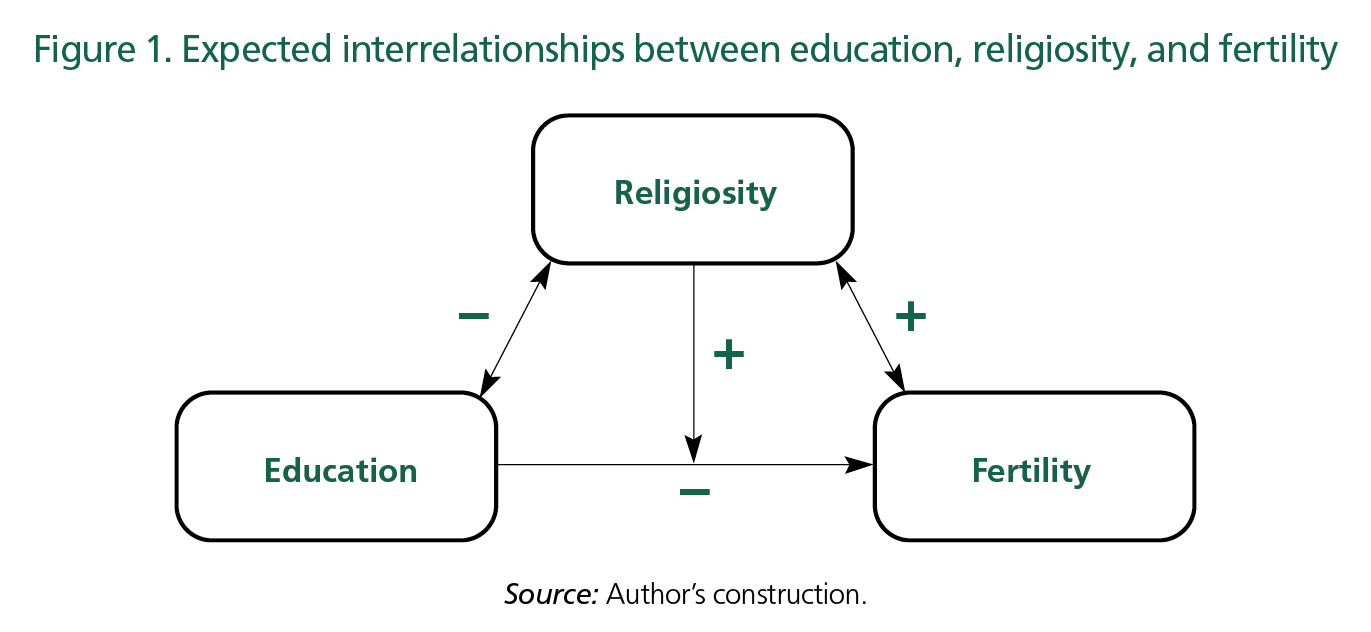

What happens to fertility when high educational attainment is combined with religiosity? Which of the two has the stronger effect on fertility? In other words, at comparable education levels, does religious affiliation moderate the education effect, leading to women without religion having lower fertility than religiously affiliated women? The expected interrelationships between the three are schematized below.

Peri-Rotem’s study uses data from a survey done in France in 2005 and another done in Britain in 2008, comparing levels of completed fertility (total number of children a woman bears in her reproductive years). Religious affiliation—to Catholicism in France and to either Protestantism or Catholicism in Britain—was measured by women’s self-identification and religious service attendance.

The study produced three findings.

In both countries, women without religion have fewer children than either practicing or nominally religious women. “Women reporting no religious affiliation have the lowest completed fertility (1.8 children on average in Britain and 1.9 in France)” in the birth cohorts studied, “whereas practicing Catholic women have the highest completed fertility at 2.5 and 2.4 children on average in, respectively, Britain and France.” Two qualifications, however: “nominally affiliated women in both countries” occupy an intermediate position, as their completed fertility is higher than women without religion but lower than practicing women; Protestant women in Britain have fewer children than Catholic women in either country.

When interrelationships between religion and education are studied with other variables kept equal, affiliated women’s fertility does not vary linearly by education level: in Britain, “for practicing Protestants and nominally and practicing Catholics, the least educated have the highest complete fertility, followed by a decline among those with upper secondary education and then a rise among those with tertiary [higher] education”; in France, among practicing Catholic women, “the highly educated show the largest family size”: 2.6 children on average, compared to 2.3 children for the least educated and 2.1 children for those with upper secondary (medium) education.” In both countries, then, religiously affiliated women’s completed fertility follows a U-shaped gradient. The expected fall in fertility as education rises is therefore moderated by the religious factor. This may be due to certain sociological characteristics: “on the one hand, family life and children are highly valued by religious communities and, on the other, women who are more religious receive more support when seeking to expand their families.” Affiliated women, then, “perceive the direct and indirect costs of children as lower than do other social groups” or non-religious women.

Average number of children by religious group and educational level

There are differences between Britain and France when it comes to the link between religiosity and educational attainment, as religion has less impact in France. There is strong social gradient in the probability of non-affiliated women having a child in Britain, whereas in France, non-affiliated women’s fertility behavior is similar whatever their education level. This may be explained by greater pressure in France to have at least one child, while women there may be less likely to postpone births because France “is characterized by a universalistic family policy with a relatively generous child-care provision” that lower the opportunity costs of women wishing to invest in their career.

Source: Nitzan Peri-Rotem, 2020, Fertility Differences by Education in Britain and France: The Role of Religion, Population 2020-1.

Related INED publication: Arnaud Régnier-Loilier, France Prioux, 2008, Does Religious Practice Influence Family Behaviours?, Population & Societies, 447.

Online: July 2020